- Home

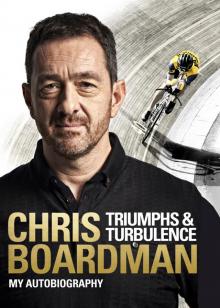

- Chris Boardman

Triumphs and Turbulence

Triumphs and Turbulence Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue: Coming Up for Air

1. The Wirral

2. Births, Marriages and Deaths

3. Barcelona

4. The First Hour: Build Up

5. The First Hour: Countdown

6. Turning Pro

7. Pro Life

8. The Tour

9. The Worlds

10. Crash

11. 1996

12. The Beginning of the End

13. The Jens

14. The Final Hour

15. Retirement

16. Secret Squirrels

17. Boardman Bikes

18. Secret Squirrels Part Two

19. The Tour on TV

20. London 2012

Epilogue: The Kids

Picture Section

Thanks

Photo Credits

Copyright

About the Book

IN JULY 1992, the virtually unknown cyclist Chris Boardman stormed to victory in the individual pursuit at the Barcelona Olympics, becoming the first British cyclist to win an Olympic medal for 75 years. Up until this point, Chris had been an unemployed carpenter, worrying that he should be earning money to support his wife and two young children instead. His historic victory on the iconic Lotus bike changed both his life and the course of British cycling.

Chris went on to break the world hour record three times, wear the yellow jersey on three separate occasions at the Tour de France, and become the sport’s best ever prologue rider. After retirement, he became a lynchpin of the revitalised British Cycling, setting up the famous R&D ‘Secret Squirrel’ club. Their meticulous attention to detail and pioneering technical know-how was crucial to the team’s success at both the 2008 and 2012 Olympics.

This is Chris’s story in his own words, from taking part in amateur time trials on the Wirral where he grew up and still lives, to the shock of sudden fame, and the compelling story of helping to build British Cycling into what would become known as the ‘medal factory’. Told with his trademark dry humour and everyman perspective, it’s a funny and engrossing story from one of Britain’s greatest cyclists.

About the Author

Chris Boardman is one of Britain’s most high-profile cyclists. He won a gold medal at the Olympics in 1992, and in 1994 became the first British rider since Tommy Simpson in 1967 to wear the race leader’s yellow jersey in the Tour de France. He lives on the Wirral, Merseyside, with his wife and six children.

For Sally

This is our book, not mine.

But you know that: you wrote as much of it as I did.

With love.

Prologue: Coming Up for Air

I was in a chamber the size of a cathedral, filled floor to ceiling with the most awe-inspiring natural architecture. Stalactites and stalagmites grew everywhere: some ten metres tall and thicker than a man’s torso; others no broader than my little finger and ready to snap at the slightest touch. Flowstone ran down the walls and between these structures like melted chocolate, disappearing into the fine white powder that covered the floor. All this ornate and delicate grandeur had stood silently in the darkness for tens of thousands of years, undiscovered until recently.

It was the most spectacular place I had ever seen and I was probably one of a handful of people on the planet to have seen it; this wasn’t the easiest location in the world to visit. I glided between two of the huge columns, careful not to brush them. As I did, my feelings of wonder and privilege suddenly gave way to a more basic concern.

How much air did I have left?

I was about a kilometre from the exit of a flooded cave 30 metres beneath the scrub jungle of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. I could simply have checked my pressure gauge to see what was left in the tank, but my third and final torch had just given out. My dive partner and I were now floating motionless in the most exquisite blackness.

Zdene wasn’t having a good day either. All three of his lights had also gone and he had already run out of air. He was now attached to me in the pitch dark via my spare regulator hose, noisily sucking up my precious reserves. Luckily, I still had my hand on the guideline. This 4 mm thick nylon thread was the only physical connection between us and the exit.

Six torch failures, two valves blown and one catastrophic loss of an air supply between us in less than 20 minutes: if I hadn’t had a big lump of plastic in my mouth I would have let out a long sigh. Instead, I groped around for Zdene’s hand, placed it on the line in front of mine, oriented his thumb towards what I hoped was our way out and gave his arm two strong pushes – the universal signal amongst cave divers for ‘Let’s get the fuck out of here’.

If we died before making it back to the beautiful Cenote Eden, the sink hole where this dive had started nearly two hours earlier, it would be the fourth time that day, so I was determined we were going to surface alive.

We swam blindly, with the thumb and forefinger of our left hands forming an ‘O’ shape around the slender line. Every few minutes our gloves would strike the rocks and stumps of old stalagmites where the guideline had been secured. In the darkness all of these junctions had to be negotiated with delicacy and precision to ensure that we didn’t dislodge the line, lose contact with it, or inadvertently turn off the route to safety and into a side passage.

After 30 minutes of silent effort, the inky blackness turned to deepest blue and finally the pale green of Cenote Eden. The emergency training drill was over: we were both still theoretically and actually alive. I hung motionless in the shallows, allowing the excess nitrogen time to slowly seep out of my blood and body tissues. I felt relieved, relaxed, at peace. At the age of 39 I’d found my element: water. But I’d had to cut through a lot of air to reach it.

CHAPTER 1

The Wirral

Stranded between the Dee Estuary and the Mersey, the Wirral peninsula struggles a bit for an identity of its own. The posher part believes it is Cheshire’s long-lost cousin, while the northern fringe would desperately like to be recognised as an annex of Liverpool – so much so that the inhabitants have been christened ‘plastic Scousers’ by the true Liverpudlians.

I grew up in the village of Hoylake, in a quiet cul-de-sac where kids played outside and dads worked on their cars. If people know Hoylake at all it’s probably for the Royal Liverpool Golf Club, one of the best links courses in the country. I couldn’t have cared less about golf, the focal point of my childhood was Hoylake’s other distinguishing feature – its huge, open-air, seawater swimming pool.

My obsession with water predates my memory of it. Long before I could swim I was perfectly comfortable being in water way over my head. My strategy was to stay below the surface and bounce up off the bottom when I needed to breathe. I was addicted to Jacques Cousteau programmes on TV. I wore my first pair of flippers to bed. My birthday present every year was a season ticket to the pool and throughout the summer months, no matter what the weather, I’d be there. When it was freezing and the place was deserted I’d be the lone figure diving under the springboards to look for change on the bottom, where it invariably fell from people’s pockets as they bounced up and down. I’d then run across the cold stone floor to the coin-operated showers and use my prize to warm up. I loved it. I wasn’t a complicated lad.

And if I wasn’t in the baths then I was in the sea, usually in my canoe, surfing in on the waves and enjoying the freedom of an unsupervised 1970s childhood.

On land, family life revolved around my parents’ great love: bike racing. On Thursday nights we’d go to Huntington, just outside Chester, where my dad would ride a ten-mile

club time trial. Afterwards we’d head to the pub next to the start area, The Rake and Pikel, and there’d usually be chips eaten by the River Dee on the way home.

At weekends we’d be woken at 5 a.m. and crammed full of toast before piling into the hand-painted family Mini Van to head off for an early morning race, my dad’s bike strapped to the roof. Afterwards, I’d hang around the kerbside results board and listen proudly for people talking about him and how well he’d done.

Keith Boardman – quiet, unassuming, sardonic sense of humour – had been long-listed for the Great Britain cycling team to go to the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, four years before I was born, but for reasons we’ve never discussed he decided not to pursue a sporting career. He settled down to life as a Post Office engineer and kept cycling as his pastime. I think perhaps my dad knew just how much pressure he could cope with and that was the moment he chose his path. When I was in the final ride for Olympic gold in Barcelona, he couldn’t bear to watch the race; he lay in the bath with a cup of tea and waited to hear the outcome second-hand. I don’t think going out to Spain and watching the event in person would ever have crossed his mind.

His talents extended to more than just riding a bike quickly. I don’t recall ever seeing a tradesman of any kind in either of the two houses we lived in while I was growing up: painting, plumbing, electrics, shed-building, car maintenance, my dad did it all and usually very successfully with not much more than mole-grips, a hammer and some black plastic tape. If our house had been powered by a nuclear reactor I suspect he’d have donned some oven gloves and got stuck in. On my seventh birthday he presented me with a homemade miniature scuba set: he had fashioned the tanks from a pair of plastic GPO cylinder-shaped cable junctions and some plumber’s copper pipe. I was ecstatic and spent many happy hours walking around our cul-de-sac wearing them.

Even well into my twenties, whenever I got stuck with a piece of cycle mechanics or electrical wiring in the house, I’d call Keith, who would always find a way to fix the problem, no matter what it was, using only materials within a two-metre radius of his position. It was a dark day when he retired from the Post Office and his ready supply of PVC tape dried up. He still has the mole-grips.

Even now, having spent most of my adult life around athletes, I can honestly say that my mother, Carol Boardman, is the most ferociously competitive person I have ever met. A cook at a local nursing home, she has always been full of energy, which is fortunate because she is a stealth combatant: one of those individuals who can quietly turn anything into a contest. Like my father, she had been a racing cyclist of some promise, finishing just behind the legendary Beryl Burton on one occasion at an event in the Isle of Man. When my sister Lisa and I came along, the demands of racing and home life became too difficult to juggle so she retired, but that didn’t stop her trying to get her fix in other ways.

On the ten-minute walk to my Nan’s my mother would often force us to skip – it didn’t feel as strange then as it sounds now – which inevitably turned into a dog-eat-dog contest: a woman and two children frantically speed-skipping along a suburban pavement with a blue garden gate as the winning post. God knows what it looked like to people driving past. Later, I would sometimes find myself cycling the last few miles home from a club ride in a group with her. It’s standard practice for cyclists to take it in turns at the front, pushing through the air while the others sit behind in relative shelter until their turn comes. One Sunday afternoon, as I led our small bunch into the outskirts of Hoylake, I spotted in the corner of my eye a fast-moving dark shape. It was Carol launching a surprise attack, sprinting for the village sign.

Many of my childhood memories involve my mother and the outdoors, walking out over Hoylake sandbank, swimming in the deep gullies, or hunting for fossils on Llandegla Moor in North Wales after a bike race while my dad had his nap. The highlight of the summer holidays was our trip to Yorkshire for the Harrogate cycling festival. We didn’t have a lot of money and I don’t think hotels or holidays abroad were ever an option. It might only have been the other side of the Pennines but it felt like a magical foreign land.

Each year we’d arrive at The Lido campsite in Knaresborough, unfold the wings of our trailer-tent and that would be our home for the next two glorious weeks. Our parents slept in one wing while Lisa and I had the other, but I preferred to sleep underneath, with the trailer’s tarpaulin as a groundsheet and a dinghy for a bed. I can still remember waking to the blue light filtering through the canvas, the smell of the grass and the sounds of sheep and distant birds. Dad would ride his various races while we battered around the park barefoot with the other cyclists’ kids, climbing the rocks around the River Nidd and daring each other to jump off cliffs into the brown water. Once we got hold of a life raft and sailed it over a weir. It was a wonderful time, a working-class Swallows and Amazons.

Up until the age of eleven, I didn’t care what bikes looked like. They were strictly for entertainment and transport, vehicles to tear round childhood on. Then shiny BMX machines began arriving in the shops from America and suddenly bikes became cool, covetable objects in their own right. In the run-up to Christmas 1979 I hinted shamelessly, leaving the mail-order catalogue open on the kitchen table at the appropriate page. My parents, though, wanted me to have the same experiences growing up as they’d had with their friends, and on Christmas morning I ran down to the front room to find a second-hand blue Carlton racer. I was secretly gutted. Or perhaps not so secretly, because 12 months later they bought me a bright red Raleigh with yellow mag-alloy wheels. The Carlton was instantly consigned to the shed and I spent Christmas Day 1980 riding my BMX in the road for two or three minutes at a time before coming back in and cleaning it for an hour. It was my pride and joy.

Water, though, still exerted the stronger pull, and if I needed any kind of push there was Uncle Dave. Dave Lindfield, my mum’s younger brother, was everything an uncle is supposed to be: mischievous, childlike, not wholly responsible. Dave and his wife Mo didn’t have children of their own then, so Lisa and I often got spoiled by them. When I was ten he bought me the most heavily used item of my childhood, a tiny wetsuit. Encased in neoprene, I could belly flop off the springboards of Hoylake pool with complete impunity.

In 1981, for my 13th birthday, he arranged for me to have an introductory session with the local sub-aqua club, who were on the lookout for new members. It was the most amazing thing I had ever experienced, BREATHING UNDER WATER! I was so smitten that even though the club wouldn’t actually train me to dive because of my age, I persuaded my mum and dad to enrol me anyway. So on Thursday nights my mother would take me to Neston pool, where she sat patiently while the instructors did their best to tolerate me. After several weeks of doing the same thing, holding my breath a lot, the novelty began to wear off. I still loved water – being in it and under it – but I was frustrated at not being allowed to go further.

My mother was frustrated too, not that she ever said so, as Thursday was supposed to be Huntington night – time trial, pub and chips by the River Dee night.

*

‘Five, four, three, two, one, go. Good luck!’

It was a warm, dry evening with a light breeze blowing when I got my first ever countdown. I’d heard the starter recite his mantra many times before, but never directed at me. During that summer of 1981 I’d begun pestering my parents to let me have a go in one of the Thursday night club races. They were the scene of many people’s first competitive experience and it wasn’t unusual to see entrants turn up to take the start in cut-off jeans or football shorts.

Mum and Dad were reluctant to give their consent, for a number of very good reasons. I’d already disrupted the rhythm of family life by insisting Mum take me to the pool on Thursdays instead of going to watch Dad race. And I’d already rejected the racing bike they’d bought me. Now, I was proposing to give up the lessons they’d paid for, along with the flashy BMX, and take up time trialling. They saw it as yet another fad and they were right. I was curious, no mor

e than that, and just fancied having a go at a race. Eventually, perhaps because it was an activity they could relate to better than my desire to swim about underwater, they relented. The neglected Carlton was retrieved from the shed.

I charged off down the road like my life depended on it, with no idea about anything as sophisticated as ‘pace judgement’. The next ten miles was a series of all-out charges followed by grinding to a near halt as I sucked in air through every orifice in my body, trying to recover. As soon as the nasty burning feeling in my lungs subsided, I repeated the process. This vicious cycle went on for 29 minutes and 43 seconds.

The beauty of the event was that despite posting one of the slowest times of the evening, I wasn’t obliged to compare my performance with anyone else’s – that time was mine. So I chose what for me was a new way of thinking, to forget everyone else and have a competition with myself. I wanted to see if I could better my mark. The following week I lined up again with a new strategy. It was called ‘Don’t start a ten-mile race with a sprint’ and the result was a time more than a minute faster than I’d managed in my first go. It was a satisfying experience, to have taken my own ideas, tested them and got a positive outcome. It didn’t escape my notice, either, that there were now several names below mine on the piece of A4 paper taped to the lamp post by the finish line. I wanted to do it again.

One of the regular timekeepers back then was an elderly man called Alf Jones. Late that summer, at one of the final events of the season, Alf presented me with a challenge as I lined up for the start. It was a light-hearted, spur-of-the-moment offer that would change my life: ‘I’ll give you 50 pence if you can keep Dave Lloyd from catching you until Aldford Bridge.’ Dave Lloyd was an Olympian and had been an accomplished professional, riding for Raleigh on the continent. He’d also won more national time trial championships than I could count. Since he lived on the Wirral himself, he’d turned up at the race for a bit of training and was scheduled to set off one minute behind me. Aldford Bridge was the midpoint of the outward leg, some two and a half miles away.

Triumphs and Turbulence

Triumphs and Turbulence