- Home

- Chris Boardman

Triumphs and Turbulence Page 27

Triumphs and Turbulence Read online

Page 27

That evening, my hopes of celebrating by closing in on the consecutive-curry record set in Delhi were dashed. I was drafted in by British Cycling’s Policy and Legal Affairs Director, Martin Gibbs, to make an appearance on BBC Two’s Newsnight to discuss cycling, both as a sport and a viable alternative to driving.

My first foray into the world of transport policy had been in 2003 when I’d sat on the National Cycling Strategy Board, a body set up by government supposedly to advise on ways to increase cycling. It took me just under two years to realise there was zero appetite to do anything meaningful to achieve the stated goal and that setting up the committee represented the entirety of government action on cycling. I resigned soon after.

Now, though, the climate was different. The unprecedented success of the GB team ever since the Beijing Olympics had given both the general public and the press an awareness of cycling that had been missing a decade earlier and their interest seemed to be intensifying. Something which had been viewed by many decision makers as a frivolous leisure pursuit that got in the way of the serious adult business of driving was now being discussed as a genuine transport solution.

It was an easy cause to champion: it lowered pollution, reduced congestion, improved health and was cheap to implement. There was just no logical downside to cycling as a means of transport. In a civilised society it should have been the obvious way to get about, particularly since nearly 70 per cent of UK car journeys were under five miles. Yet despite the mountains of evidence in favour of promoting cycling – much of it generated by government departments – many in Westminster were just as uninterested in two-wheeled transport as they had always been. They simply didn’t like it and had no intention of letting facts guide their decisions. Unfortunately for them, public opinion and a good press were something that couldn’t be ignored. But the smiles and positive words would never lead to actual change unless some traction could be gained while the sun was shining on the sport. That’s why my appearance on a programme that usually dealt with matters of state was so important.

The interviewer, Emily Maitlis, was used to grilling thick-skinned politicians so I wasn’t sure what to expect. In this instance, it seemed neither was she; I was given a very easy ride and was able to segue from Olympic sport to extolling the wider virtues of cycling without challenge. Perhaps because it was novel to see a former athlete on a grown-up programme, my Newsnight appearance caused quite a stir. For me, this period marked a new relationship with cycling; I became an advocate, a political activist for the two-wheeled cause.

For the rest of the week, I commentated on the track racing alongside Hugh, hardly believing what I was seeing. I’d thought we had made a rod for our own back in Beijing by showing just how much technology could enhance performance. It had seemed like an invitation to the opposition to spend the next four years emulating the GB approach, so I’d come to London expecting to see a much closer contest. Instead, what I was witnessing, with increasing delight, was the other nations using the same equipment, clothing and techniques as they had at the previous Games. To my mind, this was tantamount to negligence on the part of their national associations, but an unexpected gift for a GB team on home soil.

It’s one thing to have a technical advantage, but no amount of clever carbon can help individuals deal with pressure, cope with career-defining challenges measured out in millimetres, or make good decisions in less than a heartbeat. Throughout the week, British riders showed themselves able to deliver lifetime bests on demand: Laura Trott displayed the most sophisticated bike-handling skills I have ever seen to win the inaugural Olympic omnium event; her boyfriend Jason Kenny surprised everyone by taking the men’s sprint title; and Victoria Pendleton, in her last event before retirement, bounced back from disqualification in the team sprint to take gold in the keirin.

The performance of the Games, though, came from Chris Hoy. On the final night of track competition, the Scotsman added to his gold in the team sprint with victory in the keirin. That brought his lifetime total of Olympic golds to six, beating rowing legend Sir Steve Redgrave who was in the velodrome to congratulate him. Ten track events and the British squad had won seven of them.

Due to the security arrangements unique to an Olympics, it was almost impossible to interact with the team, but I was happy to watch from a distance. I was delighted to see riders and coaches who had been such a big part of my life for the last decade fulfil their potential, some for the first time, others for the last. I wasn’t the least bit sad that it also signified the end for me: who could have asked for a better note on which to bow out? Back in Newbury Park, we celebrated the team’s victory in the traditional BBC way: biryani and beer.

My focus at the Games wasn’t solely on cycling; triathlon was also on my radar, even though I wasn’t commentating on it. Four years earlier I’d watched a tenacious 20-year-old, Alistair Brownlee, compete at his first Olympics, and enjoyed his take-no-prisoners approach to the sport. He had made quite an impact on the Beijing race until he cracked spectacularly near the finish and fell out of the running. Alan Ingarfield had spotted both Alistair and his younger brother Jonny in 2006 and was so taken with their style that he’d backed them even before we had a company. Boardman Bikes had sponsored them ever since, so it was with delight that I watched Alistair win his Olympic title and Jonny take bronze. Our young business had supported a handful of athletes at two Olympics now and on both occasions we’d seen them win gold.

The end of my time in Olympic sport was fast approaching. As I had been in 2000 when my riding days ended, I was ready for it, excited for what was coming next and relieved that I hadn’t cocked it up at the last by trying to juggle too many balls at once. The only thing I was going to miss was the company of the people I’d grown close to along the way. It was cycling that had brought us together, and given how intense the world of sport is I knew it would be hard to maintain relationships once we were no longer working side by side. It was time for us all to move on.

As the competition drew to a close, I had one last TV duty to perform, a short interview with Gary Lineker in the Olympic Stadium at the start of the closing ceremony. After that, my time was my own.

Seeing and hearing a stadium packed with 80,000 people, all gathered together to watch the end of the greatest sporting show on earth, is a spectacular, even daunting thing to witness. Yet, despite having a prized spot from which to watch the pageantry, I felt no compunction to stay. I no longer felt as if I belonged, or wanted to. I was happy to catch a lift with one of the BBC cars ferrying celebrities and sports stars to and fro. One of them happened to be heading to the Holiday Inn where my little car was already packed and ready for the trip north, back to Sally, the kids and my stupid dog.

I settled into the seat and set the satnav: 238 miles to home. I put my earphones in, started my audio book, Iain Banks’s The Wasp Factory, and set off for the M25, using the dying moments of the Olympics as my cover to escape.

It had been bloody brilliant.

Epilogue: The Kids

Telling people how many children I have invariably gets the same response: ‘Six?!’ followed up with one of four questions:

‘Are any of them cyclists?’

‘Are you Catholic?’

‘Are they all yours?’

‘How do you cope?’

My replies have become equally standardised:

‘No, they’re all normal.’

‘I’m an honorary member.’

‘You’re asking the wrong person.’

‘Oh, you go numb after three.’

Having such a large family, it might seem strange that I’ve barely mentioned them in these pages but it has been an intentional omission. Having a fairly public life, I value being able to walk away from the spotlight and have a private existence. That said, the kids are the most important part of my life, which makes it impossible to write an autobiography without at least telling the world a tiny bit about them. My children have been a constant source of sur

prise, not least because of how different they all are from each other in both appearance and character.

Ed is our oldest and so was our learner-child; everything we did with him was for the first time. We were so young when he arrived – 20 – that in a sense we all grew up together. From the start he was a sensitive soul, scared of loud noises and reluctant to try anything new. Despite being dyslexic, as a child he loved to write, a passion that stayed with him and eventually led him to Southampton University where he studied creative writing. He was the guinea pig for one of my first parental decisions; we would not financially cosset our offspring. I thought this would encourage (force) him to get out there and make his way in the world. It never occurred to me that I might simply be teaching him to find ways to live on next to nothing. Which is what Ed did.

For the three years he was in Southampton, rather than give him a budget that he could blow on beer, Sally paid online for a weekly delivery of Tesco’s basics. If he wanted to party, he’d have to find a job. Although he couldn’t see why we wouldn’t trust him, he did condescend to help us out and sent a list of his essential requirements: ciabatta, Parma ham, hummus, extra virgin olive oil and Lavazza coffee. We laughed, before signing him up for some bumper packs of super noodles and value bread. We did send him some decent coffee, though. We weren’t monsters.

Since university, he has continued to eschew a material life and frequently spends months away, backpacking around Europe, picking grapes in Bordeaux and strawberries in Denmark. It’s a lifestyle I dare say I’d have enjoyed. But had I ever mustered the imagination to even consider it, I’d have focused on all the things that could go wrong and talked myself out of it before breakfast.

Next to come along was Harriet, who is also imaginative and courageous but in a very different way. Although not the oldest, she was the first to get her own place and move out of the family home. When she told us she had got a job looking after mentally disabled adults, I was surprised that she would take on such an all-consuming task. Only in her late teens, I was sure she wouldn’t last for more than a few weeks, but I thought it would be a good experience for her. She proved me wrong.

When someone in her care died, I was touched both by how much it meant to her and the steel she showed in dealing with a situation that would have had me in bits. ‘If you can’t change things you have to crack on with making the best of them. Someone’s got to care, why not me?’ was her response when I asked her how she coped. Five years later, she’s still in the job while simultaneously taking a degree in psychology at Liverpool’s John Moores University.

Harriet is the person I turn to whenever I can’t work out what Christmas/birthday/anniversary present to buy her mother. She never fails to bail me out.

George, sadly for him, is the closest in character to me: an obsessive and a worrier. At 14 he got interested in tennis. Rather than play a bit with friends, he became fanatical and volunteered as an assistant coach at the local David Lloyd tennis centre until he was old enough to take his LTA qualifications. Three years later, he was coaching full-time at a world-renowned academy in Boca Raton, Florida. Now back home, he has followed Harriet in studying psychology. I’m not sure how to feel about that. I suppose in a couple of years one of them will be able to tell me.

If George is a fanatic and a worrier, his brother Oscar, 18 months his junior, is his alter ego. Although 20, he still spends full days holed up in our TV room with his mates playing Magic: The Gathering. If you don’t know what that is, you’ll have to look it up online, as I had to. His favourite drink is a cosmopolitan, which must look odd when he’s in the pub with his cider-drinking student mates – he is also at university, studying chemistry. Oscar has already stated his intention not to engage with the real world. There is no history in our family of anyone going into the teaching profession – I barely made it through school – but Oscar was made for academia. With his quiet demeanour and floppy hair cascading down his bespectacled face, he is so geeky he’s the height of cool.

My youngest boy, Sonny, could not be more different from our firstborn. While Ed was quiet and sensitive, Sonny is outgoing, loud and already displaying strong theatrical tendencies. In the winter of 2010 we took him and his sister to a pantomime in Chester. Halfway through, Old Mother Hubbard asked for three volunteers. Unbeknown to Sonny, who was streaking down the aisle towards the stage, these had been chosen in advance by the producers, but such was his almost frightening enthusiasm that they were obliged to let him participate. Which he did, loudly. Having tasted fame, we’ve had to physically hold him back on several occasions since. Utterly without inhibitions, he’s quick to show emotion and will often sing or break into a dance in public. I hope his teenage years don’t change him.

Finally there is Agatha, who is a miniature version of her mother: smart, observant and calculating. By the age of eight she had established an art club at school, complete with a colour-coded project list, timetable and register. By ten she could have managed a small business. The first possession I can remember her coveting was a mermaid’s tail. After a week of meticulous research, she presented her mother with a list of the best candidates along with a price breakdown. She bought it with her own money and waited nearly six months before we went on holiday to a place where she could actually use it. At the pool, it made her the centre of attention and she soon had a crowd of admirers, which is exactly what she had planned. I have no doubt she will go far in life.

Christmases are loud and messy in the Boardman household and holidays are like full-scale troop manoeuvres. We have plenty of family gatherings and with the older children we often occupy a table at the local pub quiz. My mum and dad regularly attend these and I love to see them all together, although I’m not sure having a team of eight goes down too well with the other contestants.

As an athlete I rode the emotional rollercoaster. With highs and lows surrounding every training session and competition, my psychological responses were usually way out of proportion to the magnitude of the events themselves. Without being able to come home to an ever-expanding house full of the ultimate perspective-givers, who didn’t give a toss whether I won or lost, I’d have drowned in self-pity long before the Olympics in 1992, never mind my pro years.

I have perhaps painted a rosy picture of parenthood here, but it hasn’t all been perfect and I have plenty of regrets. During the kids’ formative years I was so wrapped up in my own passions that I didn’t pay nearly enough attention to theirs. I’ve not been the dad that I hoped I would be. Luckily for them, they have an amazing mother who has spent more than two decades running around gathering up all the slack I left.

Whenever anyone asks us for advice on bringing up kids, we usually just say we have none to give, you’ll have to make it up as you go. But if I had to offer an observation it would be this: you get what you give. Everything else is stuff that happens along the way.

One year old with a bucket and ice cream, what more could a boy want?

The gang by the River Nidd during Harrogate cycling festival, where I spent a lot of time wandering around in just underpants

My first skinsuit. Yes, I thought it looked good

With my mother, Carol, in my dancing shoes at one of the many club dinners

With my dad, Keith, post Olympics

Our wedding, October 1988. We’re wearing our official Team GB Olympic suits to save money. Left to right: Simon Lillistone, Eddie Alexander, me, Sally, Glen Sword, Louise Jones

Battling the wind in the National Hill Climb Championships, 1989

Barcelona, 1992. An unemployed carpenter seconds away from Olympic gold

The moment I realised it didn’t just happen to ‘people on TV’

Finding Sally in the crowd. She was begrudgingly forgiven for spending the last of our savings on a plane ticket

Returning home to Walker Street it dawned on me: you can’t turn this off

With Ed, Sally and Harriet posing for more cheesy post-Olympic photos featuring more fashion

faux-pas

The amazing Graeme Obree, the real innovator

A full hour record dress rehearsal in Peter Keen’s lab to see if I could cope with the predicted Bordeaux heat (Pete’s in the background). The wire going down my shorts is measuring my core temperature ...

Visibly shrunken after the successful Bordeaux hour attempt. Pete Woodworth is on the right

1997 and weight obsessed in what would be a fruitless attempt to keep up with the climbers

Elation and despair. I’m the surprise leader of the 1994 Tour, but about to lose the jersey just hours from the start of the UK stages

Making a good show of hiding my terror ahead of my first Tour de France road stage

George about to have his first drink

My first Tour lion on the podium in Rauen, 1997

The 1995 Tour de France prologue. Two minutes away from the ambulance ...

On the road with GAN boss, Roger Legeay

1998 Tour de France, Ireland. I have no recollection of this

The final hour, with Peter Keen track side, 40 seconds from the end of my career

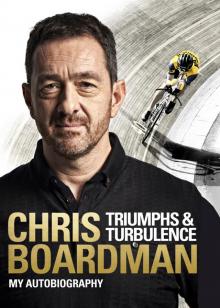

Triumphs and Turbulence

Triumphs and Turbulence